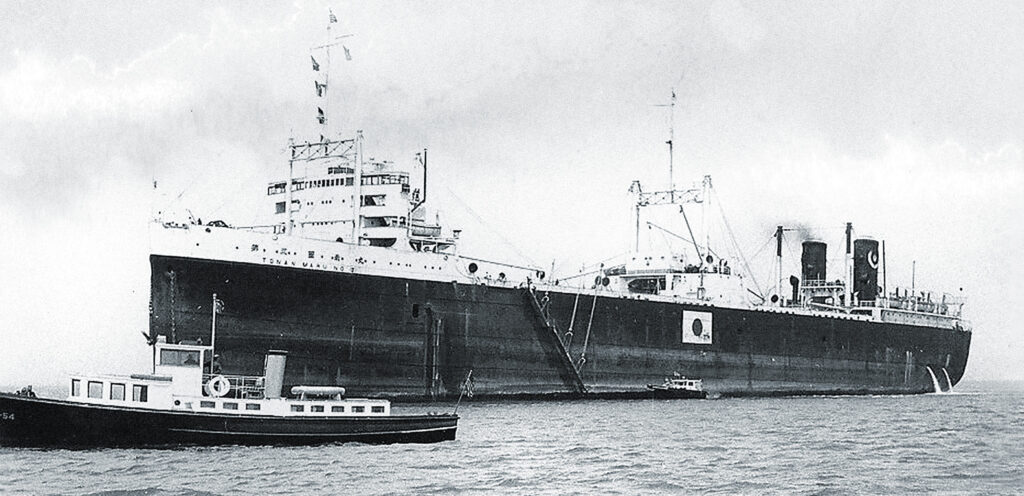

Lieutenant Commander Lawrence Randall “Dan” Daspit, captain of the U.S. submarine USS Tinosa (SS-283), was astounded at his luck. Framed in the periscope eyepiece was a 19,250-ton Japanese tanker, and it had no escort. The Tonan Maru No. 3 was making only 10 knots. It was a sitting duck.

Tinosa was on its second war patrol, having departed from Midway on July 7, 1943, to prowl the Japanese sea lanes between Truk and Borneo. On the afternoon of July 24 Daspit, having been alerted by his surface-search radar, spotted a thin trail of gray funnel smoke on the horizon. He submerged and headed for the target. Once in range, he fired four Mark 14 torpedoes at the tanker. All four torpedoes ran true. Thirty seconds later, the sonarman heard four distinct “thumps” of the torpedoes striking the hull, but no explosions. The tanker turned away and increased speed.

Daspit surfaced and began the pursuit with his diesel engines. After a long nighttime chase, he was finally in position to try again. His torpedomen checked every fish to make sure they were working perfectly. Then, coming at the tanker from the starboard quarter, Daspit fired two more torpedoes. Both hit and detonated. The muted rumble echoed through Tinosa’s hull, eliciting cheers from her crew

They had hit the tanker’s engine room. The vessel slowed to a stop.

Daspit took his time approaching the ship’s port side. He planned to fire one torpedo at a time from 1,000 yards, aimed to strike the tanker at the perfect 90-degree angle. The 680 pounds of high explosive in a Mark 14 would tear a huge hole in the hull. Two or three fish would send the vessel to the bottom. It appeared that the Tonan Maru was doomed.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

At 9:30 a.m., Tinosa fired the first torpedo. It ran straight and true, its wake a long, white trail aimed at the helpless ship. But the torpedo failed to explode. Daspit fired again. Another dud. Daspit fired again. And again. Six deadly Mark 14 torpedoes, the most advanced anti-ship weapon in the U.S. arsenal, failed to explode. The fifth one appeared to raise a tall plume of white water as a muted “Whanng!” noise came through the hull. The sixth torpedo broached after striking the enemy’s hull, then sank.

Then the tables turned as a Japanese destroyer approached. Daspit fired two more torpedoes from his stern tubes as the sub turned away. The sonarman reported two hits but no explosions. As Tinosa raced eastward, Daspit wrote in the patrol log. “I find it hard to convince myself that I saw this.” Out of fifteen fish fired, only two had detonated, and those had been fired from an oblique angle. The others were so carefully set up as to be right out of the textbook. Not one of them had exploded.

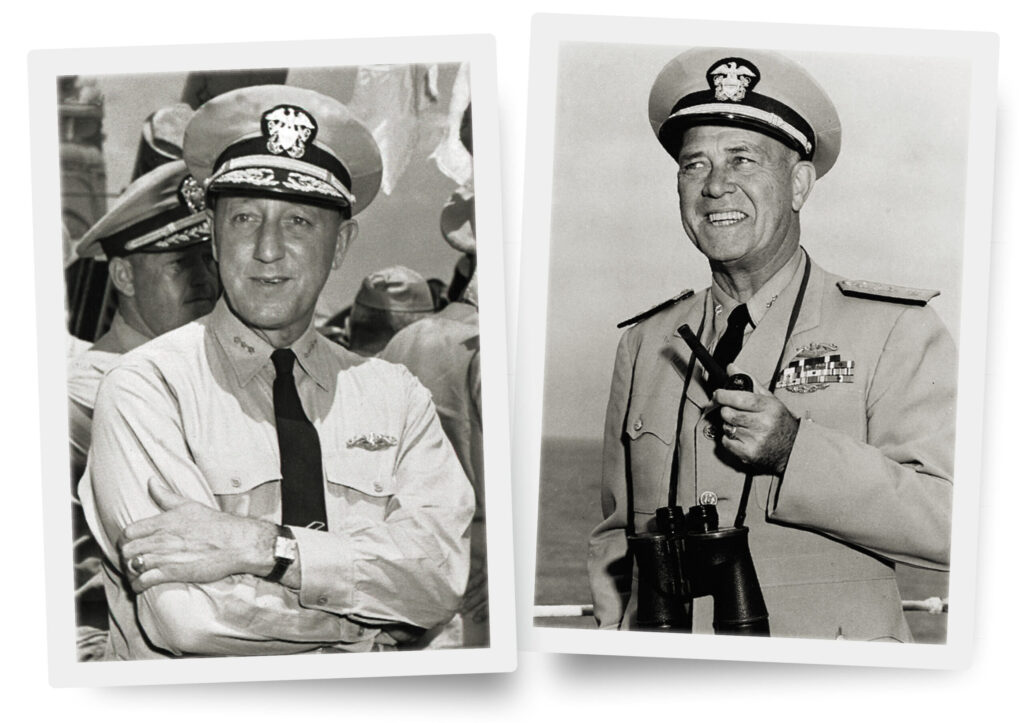

Upon his return to Pearl Harbor, Daspit was met at the sub pier by Rear Admiral Charles Lockwood, Commander, Submarines, Pacific (COMSUBPAC). A career submarine officer, Lockwood was determined and meticulous and had the reputation for giving full support to his crews. He led Daspit up to his office where the infuriated sub skipper related what happened with the Tonan Maru. Lockwood later wrote, “I expected a torrent of cuss words, damning me, the Bureau of Ordnance, the Newport Torpedo Station and the base torpedo shop. I couldn’t have blamed him. Twenty thousand-ton tankers don’t grow on trees. I think Dan was so furious as to be practically speechless.”

But when the only torpedo Tinosa brought back to Pearl Harbor was examined at the torpedo shop, it was found to be in perfect working order.

The United States submarine fleet ended World War II as one of the most effective forces of the Pacific War. By August 1945, the U.S. sank 2,728 Japanese merchant and naval vessels, for a total of 9,736,068 tons. Of those, 55 percent were sent to the bottom by American submarines.

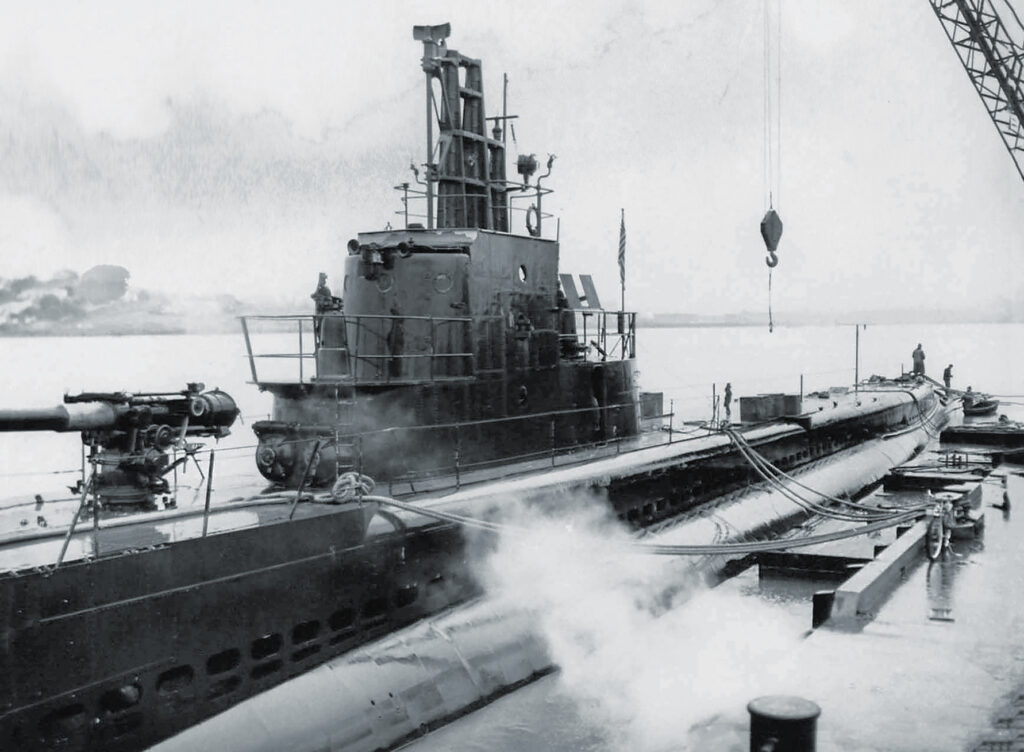

(Navsource)

But there was a period when U.S. submarines were virtually useless, even unarmed, in the savage Darwinian world of undersea warfare. That time was from December 1941 to October 1943, a total of 22 months. While there were an increasing number of excellent submarines, well-trained and motivated crews, and superb skippers, they lacked one all-important tool: good torpedoes.

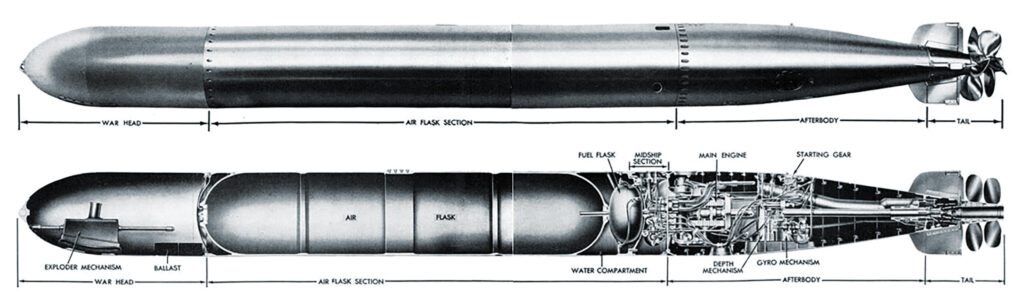

When Daspit and Tinosa had left Midway, the submarine carried 24 of the best torpedoes in the navy, the powerful Mark 14. The Mark 14 had been in service since 1931. Designed in 1926 at a cost of $143,000 by engineers at the navy’s Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd), the Mark 14s were built at the Naval Torpedo Station (NTS) in Newport. They were complex weapons that required meticulous machining and assembly. Each Mark 14 was powered by contra-rotating bronze propellers driven by a “wet heater” motor that used ethanol steam and compressed air to propel the weapon to up to 46 knots for 4,500 yards and up to 9,000 yards at 31.5 knots. It was armed with a 668-pound Torpex warhead. By 1940 each torpedo cost $10,000, five times as much as a new automobile. When the war began, nearly every U.S. sub carried the Mark 14 and its crews had full confidence in its reliability, but that confidence appeared misplaced by 1943.

Tinosa’s patrol was the most recent and extreme case of what had been a growing problem within the submarine force since the beginning of the war. From the first patrols after the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, submarine commanders complained of torpedoes that failed to work properly. On December 14 the USS Seawolf (SS-197) encountered a Japanese freighter near the Philippines and fired eight torpedoes at it. Seven missed. The one that hit failed to explode. In the first three months of war, American subs fired 97 torpedoes at enemy shipping but sank only three ships. Some torpedoes failed to explode, while others, aimed with care, seemed to run beneath their targets. Most exasperating of all, several had blown up long before hitting the side of a Japanese ship.

The torpedo’s most important component was the Mark 6 exploder. The surest way to sink a ship was to break its back at the keel, and to do that the torpedo had to explode directly under the hull. With that in mind, BuOrd designed a new exploder based on successful British Duplex and German magnetic mines. Its most important feature was the magnetic influence exploder, Project G53, which was such a closely guarded secret that even though a maintenance and operating manual had been written, it was never distributed to the submarine bases. The exploder was triggered by magnetic influence as it passed directly beneath a ship, where there was no armor. This was why the first Mark 14s carried a relatively light warhead.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

The Mark 6 also came with a contact exploder, which was a backup in case the magnetic exploder failed. It consisted of a trigger, firing pin, and detonator. The device was not much different from that of a gun, in which a firing pin hits the primer in a cartridge to cause a detonation. When a torpedo struck a ship’s hull, the collision rammed the head backward, driving the firing pin into the detonator over the warhead.

BuOrd was under a tight budget and saw no reason to spend money to test the expensive torpedoes. It conducted only one test of the Mark 6, in May 1926. Ironically, the target was a derelict submarine. Two Mark 14s armed with the magnetic exploder were fired at the sub. One ran under the target and failed to detonate. The second one exploded and sank the sub. No further testing was done.

That meant the United States submarine force entered World War II with a torpedo that had a 50 percent failure rate.

By mid-1942 submarines had fired more than 800 torpedoes in the Pacific war. Eighty percent had failed. In one instance, Lieutenant Commander Tyrell D. Jacobs of the submarine USS Sargo (SS-188) fired eight Mark 14s at a Japanese transport near the Philippines on Christmas Eve, 1941. Not one exploded.

Charles Lockwood, at that time COMSUBSOWESPAC in Australia, was listening to his own submarine skippers. He conducted an unofficial test of the torpedoes in June 1942, the first real test of the Mark 14 since 1926. Lockwood had torpedoes set to specific depths fired through a submerged net. The holes the torpedoes left in the net showed that they were running far below the depth to which they had been set, sometimes as much as 10 to 15 feet deeper. This was conclusive proof of a problem, but BuOrd dismissed the findings and blamed the submarine commanders for not setting the torpedoes properly. At Pearl Harbor, the then-COMSUBPAC Admiral Robert H. English sided with BuOrd and blamed his sub skippers for what he called their “lack of initiative.”

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

Finally, under pressure from Admiral Chester Nimitz, himself a former submariner, BuOrd conducted its own tests in August 1942, which determined that blame for the depth-setting problem lay with BuOrd. It had increased the size of the warhead but failed to make changes in the mechanism that controlled depth. The pressure sensor had been moved from the nose of the torpedo to near the tail, where water pressure became lower as the torpedo sped through the water. The lower pressure indicated that the depth was too shallow so the torpedo automatically went deeper, guaranteeing it would pass too far beneath the target. This should have been recognized long before the war, but due to BuOrd obstinacy and budget restrictions, it became an issue that sub skippers had to discover during combat.

The problems continued as late as April 1943; when Commander John A. Scott’s USS Tunny (SS-282) fired 10 torpedoes at three Japanese light carriers that month the crew heard seven explosions, but they all proved to be premature and caused no damage.

Dozens of torpedoes exploded well before reaching the target. The cause was the hyper-sensitive magnetic exploder, which was being triggered by a combination of the Earth’s magnetic field and the approach to a ship’s hull. These problems should also have been discovered and fixed long before the war began.

Nonetheless, BuOrd maintained there was nothing wrong with the torpedoes and blamed the issues on bad approaches and poor maintenance. Such obtuse stubbornness naturally started a furor among the submarine fleet. U.S. sub crews were risking their lives for nothing. Japanese transports and warships sailed on, unmolested.

After Tinosa’s cruise, Lockwood requested permission to disconnect the magnetic exploder, but BuOrd wouldn’t allow it. The submarine crews were forbidden to do anything beyond performing regular maintenance. To prevent any unauthorized tampering, BuOrd ordered that the torpedo shop at the submarine base apply dabs of paint to the screws that held the exploder mechanism to the torpedo body. Any attempt to remove or tamper with it would mar the paint. With the zeal American military men take when going against orders, some torpedomen obtained small cans of matching paint so they could retouch the screw heads after they had personally worked on the exploders.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

However, no matter how carefully torpedomen inspected and overhauled the Mark 14s, their efforts were useless. The problem was in design and materials, issues beyond the skills of even the most experienced torpedomen.

Making matters worse, politics became involved. Rhode Island, traditionally a state with strong bonds between the electorate and legislature, looked upon Newport’s NTS with overprotective eyes. One naval officer stated that “If I had the temerity to fire an incompetent or insubordinate worker, the Secretary of the Navy would be visited by both Rhode Island senators and at least one congressman, demanding the man be reinstated.” This virtually guaranteed American torpedoes would be poorly manufactured.

By 1943, the navy was building 70 Mark 14s per day, all carrying the flawed Mark 6 exploder. One of the manufacturers was the American Can Company, the primary producer of tin cans for food products. Later International Harvester and Pontiac became producers as well.

In the early summer of 1943 Lockwood, now COMSUBPAC in Pearl Harbor, flew to Washington and demanded action. This time someone was listening. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King issued an order to disconnect the magnetic exploder from all the torpedoes. But Tinosa’s failure to sink the Tonan Maru in July proved the so-called fix had not solved all the problems. The complaints continued to mount. Some torpedomen told of torpedoes they had set to run at a depth of two feet that still passed under a ship.

Lockwood took personal action. In order to convince BuOrd the problem was with the torpedoes, not with his subs, skippers, or crews, he called in Commander Charles B. “Swede” Momsen, the commander of Submarine Squadron (SubRon) 2 at Pearl. In 1939 Momsen had overseen the rescue of the crew of the USS Squalus (SS-192) after it sank off Portsmouth, New Hampshire, but his habit of speaking his mind had earned him few friends in the Pentagon. Still, he was one of the most innovative submarine engineers in the navy and he began to apply his talent to the torpedo problem.

Momsen set out to determine if the flaw lay with the contact exploder. He studied charts of the waters around the Hawaiian Islands to find a spot where sheer vertical cliffs descended to deep water and a sandy bottom. An area on the coast of the small island of Kahoolawe was perfect. Momsen, along with COMSUBPAC’s gunnery and torpedo officer, Commander Art Taylor, began supervising live firings from the submarine USS Muskallunge (SS-262) at the cliffs beginning on August 31. The first two exploded. The third one did not. Momsen himself went into the water to examine the torpedo. It had broken in two, with the warhead split. Taking extreme care, the crew hoisted the unexploded torpedo onto a barge and returned it to Pearl Harbor.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

Momsen and his team also took torpedo warheads filled with sand and a live exploder and slid them down a cable from a 90-foot tower onto a steel plate to simulate different angles and impact speeds. Seventy percent failed to explode. This confirmed something that Momsen suspected. The general belief was that the best angle to fire a torpedo at a target was from exactly 90 degrees, or broadside. But, as Tinosa’s experience demonstrated, this was not true. By studying the unexploded torpedo from the Muskallunge test and the results from the tower, Momsen and Taylor realized that a head-on impact distorted the contact exploder’s firing pin, and the forces of sudden deceleration when the torpedo hit a target slowed the pin’s motion in its track. Examination of the primers showed dents from the pin were not nearly enough to ignite the warhead. The Mark 14 seemed to be more reliable when traveling at its lower, 31-knot speed. When fired at the faster 47 knots, the firing pin was almost always damaged. The drop tests also demonstrated that a glancing impact allowed the firing pin to act properly. In other words, the best angle to fire was anything other than dead on.

Interestingly, BuOrd had made a small attempt to find the root of the problem by consulting famed physicist Albert Einstein at Princeton University. Einstein examined the Mark 6 blueprints and concluded that the firing pins were being distorted by the impact. He recommended adding a void between the outer shell and the firing mechanism. But BuOrd did not follow his suggestion.

Momsen showed his test results to Lockwood, who then took them to Washington. He returned a few days later, as he said in his official war diary, “madder than hell.” BuOrd finally admitted the exploder was at fault and agreed to design a new one. But that would take a year or more. Momsen advised Lockwood it should be possible to rebuild the contact exploder with different materials. Because the exploder had to be both light and strong, the key proved to be the adoption of exotic alloys. The machine shop at the sub base obtained light alloys from, ironically, the melted-down engine of a Japanese fighter shot down during the Pearl Harbor attack and used the metal to machine and assemble new firing pins, springs, and guide tracks. The new designs performed exactly as hoped. The project needed a lot more metal than one engine could provide, but the team found the perfect source nearby at the Army Air Forces’ Hickam Field—airplane propellers. One Army Air Forces officer reportedly said after being asked for as many damaged propellers as he could provide, “A better use for a busted prop couldn’t be found anywhere.”

Momsen was promoted to captain and awarded the Legion of Merit for his work on finding and solving the torpedo problem. He had played a significant but little-remembered role in assuring that every U.S. submarine was able to go to war against Japan with reliable torpedoes.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

With every machine shop at the sub base working on the problem, by the fall of 1943 the Pacific Fleet’s submarines were finally armed with reliable weapons. “From that moment on, all major exploder problems suddenly disappeared,” said Lockwood.

Underruns were still a concern, though. Taylor and Momsen again had torpedoes fired through a series of evenly spaced nets. The tests showed that not only were the Mark 14s running well below their set depth, they were not even running flat. They ran alternately deep and shallow, like a sine wave through the water. It was sheer luck if the weapon was at the right depth when it reached its target. This was not something that could be fixed at Pearl Harbor. It would have to go right to BuOrd and the NTS. But at least Lockwood’s skippers could make allowances for the erratic depth settings. Knowing that the sine wave had a cycle of about five hundred yards, crews could set a torpedo so it was on the high point of the curve at impact.

By the time the first reliable torpedoes went to sea, the war had been going on for 21 months. Dozens of patrols had been wasted, hundreds of American lives lost, and important enemy targets missed. Now aggressive, skilled, and innovative submarine commanders—men like Dudley “Mush” Morton of USS Wahoo (SS-238), Richard O’Kane of Tang (SS-306), and Eugene Fluckey of Barb (SS-220)—had the torpedoes they needed and were adopting the tactics to use them. They patrolled on the surface by day, keeping a sharp lookout for planes and scanning the seas with radar. This doubled the area they could patrol. With the reliable torpedoes virtually guaranteeing a kill, the men under Lockwood’s command began sweeping the Pacific Ocean of Japanese ships. All they needed was good intelligence, initiative—and luck. As Lockwood told one new sub skipper, “If you’re not lucky, I can’t use you.” It was still a dangerous game of cat and mouse, but now the fleet’s subs were no longer unarmed. They were deadly sharks hunting for prey.