Yves here. I am generally not keen about disagreeing fundamentally with the author of an article, but here I feel compelled to. Thomas Neuburger attempts to find a silver lining in modern society’s pretty much baked in collapse. Perhaps some, even many, readers will take comfort in what Neuburger says below. I find this line of thinking unfathomable.

Neuburger focuses on the supposed advantage of a collapse where a somewhat or very centralized system “collapses” by fragmenting so that lower levels of organization are no longer directed and dominated by the core but instead operate with more autonomy. And in a leap of logic, that is depicted as less oppressive. This is at best a Rousseau-ist assumption, that the state of nature is peaceful.

First, in some genuinely authoritarian societies, the reverse has been the case. Most Iraqis came to lament the ouster of Saddam Hussein. Even though he was brutal, he kept a divided society together and functioning. There was no lower level rebuilding. Iraq is a failed state. Ditto Syria under Assad.

Second, this discussion completely omits what the circumstances of this collapse are likely to be. We will see mass migration due to climate change and more wars over diminishing resources, particularly water and likely agricultural production. The interests that can wield the most force will generally fare less badly as this brutal scramble progresses. The idea that a less hierarchical, less power-driven system will emerge seems remote, at least in the intermediate phases.

The increased primacy of war-making will also increasingly relegate women to secondary status. The greater strength of men will matter again.

Trump is bizarrely accelerating the breakage of production systems which would have become on its own a driver of collapse, if disease and climate change damage didn’t get there first. Just about everything we regard as fundamental to how we live, from the Internet to transportation systems to telecommunications to our power and water systems to medicine depends on highly complex organizations and governments. For instance, our world depends on chips. What happens when their output contracts due to fights over resources? And remember, we have foolishly committed our knowledge to non-durable electronic media (save perhaps optical storage). What happens when our successors can’t readily access it?

Thomas Hobbes deemed life to be nasty, brutish and short in 1651. Future society will be lucky to descend to the level of civilization he knew. Our heirs are likely to shoot past that to an even less advanced state, in terms of application of technologies and tool production and use.

And these societies were not kind to the weak. Sickly babies were often left to die. And that’s before getting to the high toll of childhood diseases. How many of you are confident you would have lived to adulthood in a world with the medical knowledge of say, 1500? Even with our understanding of germs and the importance of cleanliness, how easy will it be to keep that up if municipal water systems are a thing of the past?

Which is all the more reason that it’s so distressing to see our supposed betters accelerating the arrival of bad outcomes with planet-destroying energy hogs like AI and Bitcoin. And I hate to see the supposedly more socially aware cohort going from Green New Deal hopium to collapse hopium.

By Thomas Neuburger. Originally published at God’s Spies

My name is Ozymandias. Miss me yet?

My name is Ozymandias. Miss me yet?

“Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.”

—John F. Kennedy

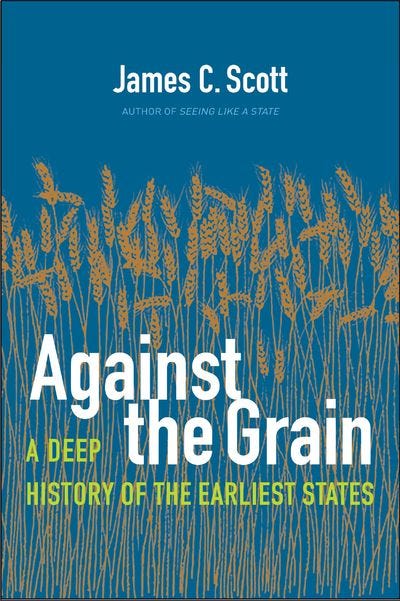

“The state and early civilizations were often seen as attractive magnets, drawing people in by virtue of their luxury, culture, and opportunities. In fact, the early states had to capture and hold much of their population by forms of bondage”

—James C. Scott, Against the Grain

I’ve been writing about how hunter-gatherer and early neolithic lifestyles are both different from the lives most in the West “enjoy” and also are viable alternatives to it. That is, there’s nothing inevitable about kingdoms and empires as a method of organizing society — it’s just what our European ancestors settled into, or were forced into by the ethnic group that overran their lands millennia ago.

For more on that, see here:

Western Life Is Only One Way to Live

Many readers have since asked, “OK, we’re stuck with our rulers — so what do we do? If living controlled in hierarchies is simply a choice made by our ancestors, how do we get out of it now? What is the mechanism of change?”

Valid questions all. I think the answers start with the ideas below.

Three Roads Home

If we think of tribal, hunter-gatherer, or small village life as “home” — after all, as a species we spent almost 95% of our time adapted to smaller, low-hierarchy communities — what’s the machine that breaks these states, these giant engines of control, so we can free our lives?

Keep in mind, those of our species who pathologically love control, will not give it up easily, no more than an emperor would change place with a salt mine slave. Not a normal abnormal emperor at least, not Jamie Dimon, say, or Elon Gates.

This means that control will have to be torn from their grasp. How? I see three ways.

• Electoral decapitation and system restructuring, whereby those in control are removed from power by organized peaceful means and the system rebuilt to be much more fit for the purpose. A transition, in other words, of both leaders and systems from oppressive and predatory engines to egalitarian and nurturing ones.

I’m not sure this option is likely, but this is the “theory of change,” as it’s called, of most sincere, progressive, Party-aligned Democrats, voters and operatives alike. Sanders supporters in his two failed runs were driven by this idea — reform the system using the system’s rules.

• Forceful overthrow and system restructuring, whereby those in control are removed against their will using unapproved means and the system rebuilt. This is the “tell, don’t ask” approach. People in control are told or made to leave, and the place is remodeled when cleared of their debris.

As the Kennedy quote above makes clear, this method often occurs when the first method fails and people have reached their limit. When asking fails, eventually telling takes over, even if it takes a while, years or centuries. All empires fall; all king-controlled states break down; all corrupt big city machines eventually lose power. Often the reason for these failures is forceful revolt — overthrow outside of constitutional means.

Marianne, the symbol of liberty, leading the French to freedom, by Eugene Delacroix (1830)

Marianne, the symbol of liberty, leading the French to freedom, by Eugene Delacroix (1830)

But we can’t say this happens all the time. Yes, all empires fall, but not always from revolt. That brings up the third reason for things to change.

• Collapse, whereby a system fails on its own, brought down by its own inadequacy or felled by an external force. A drought will do kingdoms in. Disease does the same. A meteor shattered the rule of the dinosaurs, collapse on a global scale.

And needless to say, we’re on the verge of it now — collapse of an empire that’s arguably in its last throes, by which I mean the rule of the West over all of the rest of the globe; plus collapse of a climate system that sustains every species adapted to Holocene temperatures.

The Sumerian empire fell for a combination of reasons — population shift and drought being two of them. The Aztec empire was overthrown by Western expansion — the Spanish and Portuguese hunt for global colonies — but the Mayans fell much as the Sumerians did, through drought and social exhaustion. A Greek Dark Age ended the Mycenaeans — the world of Agamemnon and Achilles — just as a Roman Dark Age ended, well, Rome.

Can Collapse Be a Good Thing?

And here’s the rub: we think of collapse as a tragedy. It’s almost built into the name. A “lapse” is a fall from something, often religion (“lapsed Catholic”), and “co-lapse” first meant a group that falls together.

“Falling” is never thought good, and we often think of temples and monuments, ruined and abandoned, romantically, as though a good thing had died.

>The Grand Plaza with the North Acropolis and Temple I (Great Jaguar Temple) at Tikal, Guatemala

We think of the building of large and oppressive social structures as accomplishments, things to desire, and we mourn their passing as though the move away from that life is a loss.

But what if that loss is a gain?

Collapse As Gain

A book we’ll be taking a longer look at shortly is James C. Scott’s Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. I first mentioned it here.

One of his theses is that these large and oppressive structures — kingdoms and empires, giant cities and states — were not good, nor were they inevitable in the sense that they represented inescapable social advances. We don’t, in other words, “move forward” to life in large states, nor do we “turn into savages” when those states collapse. That’s a romantic notion, and an illusion.

Here’s Scott on the surprising (to most) four millennia span between the rise of sedentism (small village life) and the oppressions of “civilization” (life ruled by kings).

Note the “We thought … but it turns out” structure of the passage below. There are several of these pairs. From the Preface, all emphasis mine:

The astonishing advances in our understanding over the past decades have served to radically revise or totally reverse what we thought we knew about the first “civilizations” in the Mesopotamian alluvium and elsewhere. We thought(most of us anyway) that the domestication of plants and animals led directly to sedentism and fixed-field agriculture. It turns out that sedentism long preceded evidence of plant and animal domestication and that both sedentism and domestication were in place at least four millennia before anything like agricultural villages appeared. Sedentism and the first appearance of towns were typically seen to be the effect of irrigation and of states. It turns out that both are, instead, usually the product of wetland abundance. We thought that sedentism and cultivation led directly to state formation, yet states pop up only long after fixed-field agriculture appears. Agriculture, it was assumed, was a great step forward in human well-being, nutrition, and leisure. Something like the opposite was initially the case. The state and early civilizations were often seen as attractive magnets, drawing people in by virtue of their luxury, culture, and opportunities. In fact, the early states had to capture and hold much of their population by forms of bondage and were plagued by the epidemics of crowding. Finally, there is a strong case to be made that life outside the state—life as a “barbarian”—may often have been materially easier, freer, and healthier than life at least for nonelites inside civilization.

Each of those pairs deserves its own expansion — the surprising 4,000 year span between the first sedentary villages and plant and animal domestication; the place of wetland abundance, not irrigation, in pre-state sedentary lifestyles; the fact that fixed-field agriculture long preceded kingdom and state formation; and the fact that the agricultural life was not a step up in leisure, but exactly the opposite, a life lived as slaves to the land.

But for now look at the last point — The early states had to capture and hold much of their population by forms of bondage and were plagued by the epidemics of crowding.

There’s nothing romantic or desirable about living in crowds and filth (think Medieval cities and towns). I’ll add without citing for now David Graeber’s similar observation, that many hunter-gatherer tribes who tried fixed-field agriculture abandoned it later, just as the shepherds forced into British industrial hell-towns and factories would have loved to go back, if only their masters had not taken their fields away along with their freedom.

Escaping Civilization

This leads us to think about collapses differently. From Scott’s Chapter 1:

In unreflective use, “collapse” denotes the civilizational tragedy of a great early kingdom being brought low, along with its cultural achievements. We should pause before adopting this usage. Many kingdoms were, in fact, confederations of smaller settlements, and “collapse” might mean no more than that they have, once again, fragmented into their constituent parts, perhaps to reassemble later. In the case of reduced rainfall and crop yields, “collapse” might mean a fairly routine dispersal to deal with periodic climate variation. Even in the case of, say, flight or rebellion against taxes, corvée labor, or conscription, might we not celebrate—or at least not deplore—the destruction of an oppressive social order? Finally, in case it is the so-called barbarians who are at the gate, we should not forget that they often adopt the culture and language of the rulers whom they depose. Civilizations should never be confused with the states that they typically outlast, nor should we unreflectively prefer larger units of political order to smaller units.

Collapse as re-fragmentation. Not death, but rebirth, reconfiguration. The United States un-united, regionally governed. China the same. De-growth and de-globalization. Local control. More choices.

I’ll stop for now, but please consider that thought. Collapses aren’t always terrible tragedies, with fires and armies and death. They’re often just places abandoned because no one wanted to stay. The city collapses, yes, but its people now thrive, living separately, simply and well. No big screen TVs perhaps, but supportive communities replace heartless billionaire kings intent on their own aggrandizement at others’ expense. Fair trade? You’d get to choose.

Of course people will die, especially if the inevitable climate rears its head, but those consequences are, frankly, already baked in. We’ll have them whatever we do. What will come out of that may be a blessing, not “collapse” in the tragic sense, but a wipe of the slate, a chance to construct a much more humane life.

If orderly restructuring fails (it’s failed so far), is “collapse” as considered above worse than violent revolt? I think I might choose the former, however hard, over the kind of great civil war we would otherwise get.

Source link