The Fighting for This Italian Town Was so Brutal They Called It the Stalingrad of the Adriatic

The Hastings & Prince Edward Regiment—a Canadian unit known as the Hasty Ps—were ordered to relieve the 1st Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers—the Faughs—on the afternoon of December 5, 1943. As part of the British Eighth Army under Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, the two units had been fighting their way up Italy since crossing over from Sicily in September and were now approaching the Adriatic coast somewhat less than halfway up the Italian boot. Lieutenant Farley Mowat, the Hasty Ps’ intelligence officer, had gone forward with the intelligence officer from the Faughs. Rain pelted down. Files of Faughs were coming out of the line. “Their faces were as colourless as paper pulp,” noted Mowat with mounting dread, “and they were so exhausted they hardly seemed to notice the intense shelling the coastal road was getting as they straggled down it.”

The Faughs might not have been noticing, but Mowat was. He had been leading a platoon when the Hasty Ps landed in Sicily in July and he felt like the ensuing months of combat had brought him near the breaking point. As he watched the Faughs, the pervading and rancid smell of cordite hung in the air. His heart pounded and jolted in his chest without rhythm. He began to shiver, although he was not cold. Everything told him to stop, turn round, and run. Pulling out a cigarette, he offered one to the Irish lieutenant, who lit a match in cupped hands. But Mowat turned away. “For in that instant,” he wrote, “I realised what was happening to me. I was sickening with the most virulent and deadly of all apprehensions…the fear of fear itself.”

They walked on, reached a ridge, and lay on their stomachs among some sodden bushes. Low cloud obliterated the view. This was a strange landscape: a series of plateaus, gently undulating but rather flat, on which stood villages, farmsteads, and endless vineyards, olive groves, and meadows. Scoring these plateaus, one after the other, was a series of gullies, most quite narrow and verdant—covered with acacia, baby oaks, and low-growing bushes. Mowat could see little but ahead lay the Moro Valley, plunging steeply perhaps 200 feet from the edge of a plateau to the river. Tracks wove their way down past more vineyards and olive groves to cross the Moro itself, no more than 10–15 yards wide, but below deep, steep banks, and then climbed back up to a series of villages—Villa Rogatti, the hamlet of La Torre, and San Leonardo, which on a fine day could be seen very clearly, a collection of white and stone houses sleepily huddled together. The valley itself was only two-thirds of a mile wide. From Mowat’s position the coast was a mile distant, if that. The fishing village of Ortona, their initial objective, could be clearly seen, perched on the edge of the sea, a little way to the north. So close one could almost touch it.

(National Archives of Canada pa167913)

Yet, as was so often the case in this ancient land, the landscape favored the defender. Crossing the valley, already zeroed by German artillery and mortars and teams of machine-gunners, would be brutally tough. The gullies—narrow gashes into the plateau covered with trees and vegetation—were ideal for placing mortar teams. Each of these gullies, some long, some quite short, ran towards the sea and against the flow of the Allied advance. And for all the support of the artillery behind them and even tanks, taking this ground was really a job for the infantry: men who would have to thread their way off the plateau, down into the valley and up the far side, and hope there would be enough of them still standing to prise the enemy from their positions.

Also now up on the southern side of the Moro were the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada. Major Roy Durnford, the padre, had been shocked by the scenes of desolation as they’d neared the Sangro River to the south two days earlier. “The river and banks are profuse with battered remains of war and a completely ruined bridge,” he noted. “Dead strewn about—all German. God help our lads.” For those entering this war-torn landscape there was a terrible, gnawing sense of approaching hell. On both sides of the Bailey bridges over the Sangro were immense furrows of mud as well as battle debris. Durnford crossed the river on December 3 and immediately saw large numbers of new crosses. A barrage was in full swing, and ahead stood the village of San Vito. Durnford thought the remains of the hamlet and the surrounding landscape were worse than anything he’d seen in terms of absolute devastation.

The changeover was complete on the evening of December 5 and, as Farley Mowat discovered when he reported back to Major Bert Kennedy, the Hasty Ps’ acting commander, they were due to attack straight away, that night, and silently too, without any artillery softening up the enemy first. Major General Chris Vokes, the 1st Division commander, believed that a silent, stealthy attack was their best chance of success. Vokes, who had only taken command at the end of September, was a professional soldier, taciturn and with a reputation for pushing his men particularly hard.

Kennedy, frantic at the speed with which they were expected to be ready to launch this assault, now ordered Mowat to head back again and find a suitable crossing point over the river. The thought of such a patrol was making Mowat sick to his core; he knew that four months earlier he’d have been eager for the chance and that even two months ago he would have undertaken it without too much thought. But not now. Orders, though, were orders. Collecting some scouts, he willed his way forward and together, scrambling down the vine-covered slopes, they safely reached the Moro, waded along its overflowing banks until they found a fordable spot, then scampered back up again. Not a shot had been fired, not a single enemy soldier had been heard. Mowat had survived.

(Brian Walker)

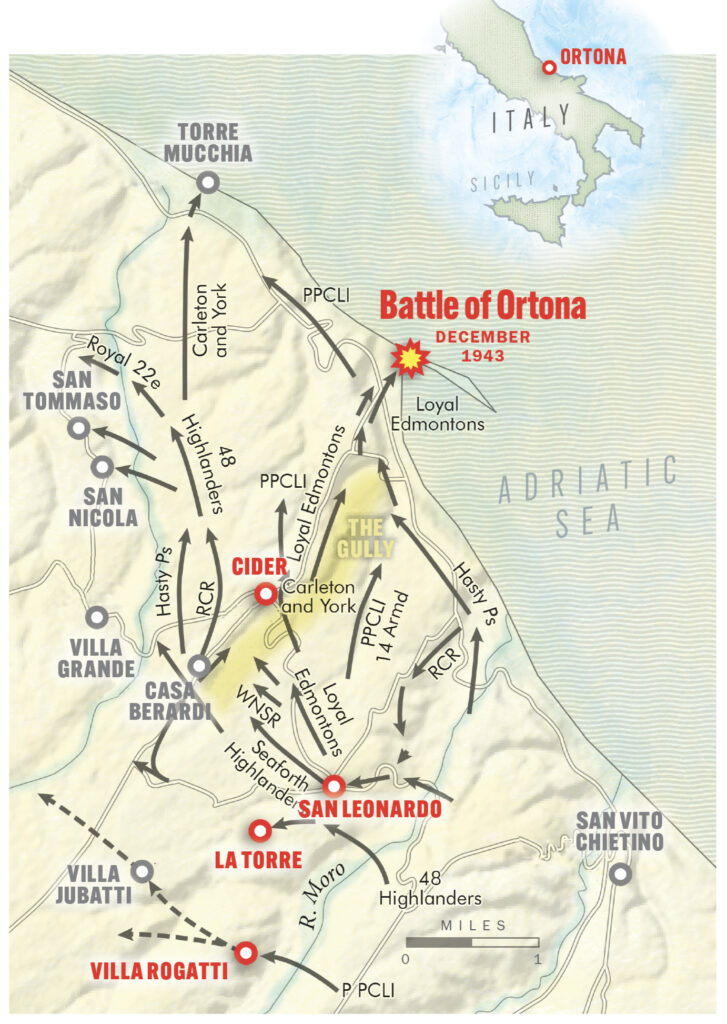

Vokes’s plan was to launch three battalion assaults. The Hasty Ps would be on the right, near the mouth of the Moro, close to the sea and the main Highway 16 heading north. In the middle would be the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada aiming for the village of San Leonardo, perched on the plateau on the far side of the valley; and then on the left, the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry—the PPCLI—would attack the next settlement along on the north side, Villa Rogatti. Three crossing points, three bridgeheads, and from there they could push forward across the plateau and take Ortona. Vokes had identified a crossroads that stood above the southwest end of a particularly long gully just to the south of the town as a key objective. Here, the track north from the plateaus and gullies crossed the main lateral road—and, immediately parallel to the road, the railway line—that wound its way towards the village of Orsogna, 12 miles southwest of Ortona. Vokes code-named this objective “Cider.”

Behind the Canadians, back on the Sangro, the torrential rains that had accompanied them on their journey north had caused the river to flood and all three Bailey bridges had been swept away. The engineers would have to start all over again, but a more immediate concern was the halt in supplies this caused. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade hadn’t even reached the Moro front yet.

Nonetheless, at midnight the attacks began. Mowat watched Able Company head off, his old platoon from Sicily leading the way. Down they went, into the valley, and then silence. No artillery, no firing. The rain continued; it could be heard beating a drum on the leaves and on the track. Then suddenly, starkly, cutting across the night, the buzz saw of machine guns, flares crackling overhead and fire from the enemy artillery, shells screeching and sucking their way across the valley. The battle for Ortona had begun.

The fight turned into a proper meat grinder for both sides. Over 36 hours between December 9 and 10, the Germans launched no fewer than 11 counterattacks on the Hasty Ps’ fragile bridgehead on the ridge by the coast road, on the north side of the Moro and to the east of the battered village of San Leonardo, all of which had cost considerable blood to the German 200 Regiment, but which had also chipped away at the Canadians. Somehow, the Hasty Ps had held on.

(IWM NA 10203)

Then, on Saturday, December 11, new orders arrived for them to break out of their bridgehead and attack north. The assault was to be launched at 4 p.m. that afternoon, while it was still just about light, and despite the suicidal nature of the order it was merely a diversion from the main event, which was an attack by 3rd Brigade from the ruins of San Leonardo. “Once again,” noted Farley Mowat, “we were to be the goat in the tiger hunt.” He was at Battalion HQ on the ridge, a collapsed shed, peering out over the sea of mud, blasted farm buildings, burned-out tanks, and the flotsam of battle and shattered vines. A scene of utter desolation, made worse by the gray of a winter afternoon sky. Suddenly, something moving caught his eye, and training his field glasses he spotted two huge pigs eating the bloated corpse of a mule. He knew they would be just as happy to gorge on dead soldiers.

A squadron of Sherman tanks arrived at 3 p.m. and to Mowat’s horror Kennedy ordered him to accompany them on foot and to be the point of liaison with the infantry. It wasn’t until 5 p.m., though, that the attack finally went in and, just as the Hasty Ps had expected, there was no sign from the Germans to suggest they thought this was a diversion. Artillery and mortars came crashing down; the raucous din was so immense that Mowat could hardly hear the engine of the Sherman behind which he was crouching. Meanwhile, Baker and Charley Companies, up ahead, disappeared, enveloped by the smoke and fog of war.

In fact, the attack went better than Mowat, for one, had feared, because the German infantry had already pulled back in their sector; and because of the mud, the shelling and mortar fire were less lethal than normal. Even so, when a salvo of shells whooshed in and crashed nearby, Mowat fell on his face in the mud and at that moment something snapped within him. Getting to his feet, he turned and hurried back, past the ruined shed where the newly promoted Lieutenant-Colonel Bert Kennedy was sheltering and on to the pockmarked coast road heading south. He’d not gone far, however, when Franky Hammond, commander of their anti-tank platoon, speeding forward with a jeep and a 6-pounder, stopped and grabbed him by the arm.

“Drink this!” he told Mowat, thrusting a rum-laced bottle of water in his hand. Mowat drank. “Get in the jeep,” Hammond then ordered. “Now show me the way to BHQ.”

This seemed to snap Mowat out of his fear-induced stupor. He did not desert that evening after all.

(National Archives of Canada pa131064)

Vokes still aimed to reach the crossroads code-named “Cider,” and while the Hasty Ps were launching their diversionary attack along the coast road he sent 2nd Brigade and the newly arrived 3rd Brigade into the fray. To reach the “Cider” crossroads they had to cross another of the strange, narrow, wooded gullies that so marked this landscape, although this particular one, stretching far to the southwest of Ortona, was named simply The Gully. They tried to attack directly across it, but the Germans, hidden until this point, appeared from the depths of The Gully as the leading Canadian infantry approached and stopped them in their tracks. Four counterattacks followed the next day as the rain came down once again. It was the turn of the Canadians to attack once more on December 13, and again they got nowhere. Nor were these men from 90 Panzergrenadier–Division anymore but paratroopers of 3 Fallschirmjäger-Regiment, who, like the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade, had been moved up from the Castel di Sangro sector of the upper Sangro.

To the northwest, the brutal fighting for Ortona continued as the Canadians inched towards the “Cider” crossroads on the far side of The Gully. All along this ridgeline, separate battles were playing out as the landscape, thick with smoke, often low cloud, rain, and fog, made orientation very difficult. The southern slopes of The Gully were steep and made of thick, soft clay: banks that were easy to dig into but also almost impossible to hit by shellfire because of the angle of the shell’s arc. Even mortars, which had a steeper plunge, struggled to hit the southern bank. Farther west, at the extremity of The Gully, German artillery had the ground liberally mined and zeroed, while on the ridge beyond to the north further troops were dug in with machine guns. These fired over the top of The Gully at any approaching attack. It wasn’t until evening on the 20th that at long last the “Cider” crossroads, halfway along The Gully on the northern bank, was in Canadian hands.

The struggle for Ortona was becoming one of the most brutal fights of the entire Italian campaign to date. The fighting for the town itself was underway by December 23, as the defending Germans attempted to corral the Canadians into carefully prepared killing zones. The piles of rubble were laced with booby traps, while the paratroopers were able to use their machine guns very effectively; each Fallschirmjäger-Gruppe of ten was issued with two MG 42s rather than the single one that was standard for all other infantry. It meant that buildings on either side of the narrow streets were used as MG positions, and placed on different floors, too. Within Ortona’s narrow streets the raucous din of battle was terrible, the whine, whump, and crash of shells and almost never-ending chatter of small arms, sharp and jarring. More tanks inched forward, the infantry crouching behind. The turret swiveled then the gun fired, the shell crashing into the building. Smoke, dust, bricks, stone, and masonry tumbling. Room by room, house by house, Germans were forced back. Only when it grew dark did a bit of calm return.

(Library and Archives of Canada pa-163936)

There was little sense of confidence, hope, or Christmas cheer at Ortona, which had descended into a bitter street battle. The Canadians had not been trained in urban operations and the number of snipers and hidden machine guns had taught the tank men of the Three Rivers Regiment to simply pummel every building. Pushing behind and alongside them were the Loyal Edmontons—the Eddies—and the Seaforth Highlanders, the battalion that had first tried to storm San Leonardo a lifetime ago at the start of the battle. Liberal use of Brens, Tommy guns, and grenades was the only way in fighting that had been floor by floor, not just house to house. Rather than risk tripwires and booby traps on the ground floor, they were soon discovering that it was better to knock down walls that hadn’t already been blasted, lob in grenades and clear each house like that. At no point, though, did the Fallschirmjäger show any sign of throwing in the towel; men of the Seaforths came across one Fallschirmjäger who had been blinded by shrapnel but was still waving his weapon. “I wish I could see you,” he yelled in English, “I’d kill every one of you.” They were starting to call Ortona the “Stalingrad of the Adriatic.”

“Jerry sending shells over,” jotted Roy Durnford on Christmas morning. “Deathly chatter of machine-guns. Rumbling of falling buildings, roar of guns.” He had headed to the church of Santa Maria di Costantinopoli at the southern end of the town. Tables had been set for the companies to sit at and have a Christmas meal, and roses and violets placed in small cups of water to add a little cheer. “Shells whine and explode,” he scribbled. “Holy Night. The meal for C Company. Brigadier and Colonel cheered. The faces of new recruits…Orders to leave for the front—a few hundred yards forward. A Coy [company] returns from front. Weary, strained, dirty.” He collected them for carols in the cloisters, which he was careful to make voluntary, then they repeated the meal again. And the entire occasion was repeated another time when B Company came in, and finally again when it was D Company’s turn. The fighting in Ortona, Durnford reckoned, followed a quickly established routine: “We shave same house, exchange grenades and shoot at his head if out of window and he at ours.”

On Christmas, Farley Mowat was in a farmhouse in a salient west of Ortona that was now the Hasty Ps’ Battalion HQ. Early that morning a wounded sergeant arrived with the news that Major Alex Campbell, Mowat’s former company commander, had been killed charging at the enemy, his body riddled with bullets and falling into the mud and jerking until the life was drained from him. Mowat was still struggling to take in what the sergeant was telling him when the blanket screening the cellar doorway was pulled back and two stretcher-bearers pushed in carrying his friend Al Park, alive, but only just; he had a bullet wound to his head. As Mowat looked at his pale, ghostly face and the blood-stained bandages around his friend’s head, he felt tears well and then stream down his face. It was Christmas Day, 1943.

(National Archives of Canada pa167915)

There had not been a lull all day, nor on the day after. Inside the town, on the morning of the 27th, Siegfried Bähr of the German 2 Bataillon learned that his unit had just sixty men left. Once again he heard the rumble of tanks, the clatter and squeak of tracks, then the pause, followed by the shot of the main gun and the explosion and rumble of masonry that followed. Canadians were crawling over the roofs, through the upper floors. He could hear machine guns crackling, hand grenades bursting. “The battle rages on,” noted Bähr. “Leutnant Heidorn stands in the archway of a gate and secures a clear path with his machine gun. Suddenly a hand grenade falls in front of his feet and he quickly retreats. The Tommies are already in the same house on the upper floors. The Leutnant runs up a half-destroyed staircase. We hear gunshots, hand grenades explode…We have to leave the house, the Leutnant has fallen.” No, not fallen, Bähr then thought, that was a stupid word to describe it; after all, someone who fell over could get up again, but Heidorn wouldn’t. He was dead, no more, lying in a growing pool of blood amid the dust and debris of yet another shattered house, in a nondescript street in a small coastal town halfway up the leg of Italy.

They scuttled to a new building, Bähr holding the radio link by a blasted window, the rest of the men looking at him and wanting to know what they should do, and when reinforcements might come. “Absolutely resist!” was the instruction, repeated yet again. But how? And what with? Leutnant Ewald Pick, whose best friend had just been killed by a grenade, looked dejected. He asked Bähr for a cigarette, then lit it with a trembling hand. Suddenly, without saying a further word, he dropped his machine gun and stepped out of the house and into the piazza outside. Bähr and the others watched, aghast. At the fountain, Pick stopped and crouched, smoking his cigarette, then pointed at a Canadian on the second floor of a building across the square. “All weapons,” Pick shouted, “fire at will.”

From their building, Bähr and the others yelled at him to come back, but then a shot rang out and Pick collapsed. He had been the last standing officer in 5 Kompanie. Only once darkness had fallen did Bähr and another man scamper out to fetch him. He’d been shot in the lung, but was still alive. What a waste. Carefully, they took him to the aid post, but he died there soon after, in the early hours of December 28. Bähr hurried back and then a radio message arrived that, at last, they were to fall back. “In the middle of the night, in single file,” noted Bähr, “we leave Ortona, heading north, stumbling on the slope of a vineyard, almost in the direction of the homeland.”

The Battle of Ortona was over.

James Holland writes World War II’s “Need to Know” column and is the author of Brothers in Arms, Sicily ’43, Normandy ’44, Big Week, and other books. This article is excerpted from The Savage Storm © 2023 by James Holland. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.